In a magnetic material, a paramagnetic phase, in which the material shows weaker temporary attraction when exposed to a magnetic field, is attained at a temperature higher than the ferromagnetic phase. Surprizingly, the hotter paramagnets, even by travelling longer distances, thermodynamically, undergo faster transitions to their ferromagnetic phases, shows a new study.

The research which establishes a phenomenon called Mpemba effect, earlier found in water, to be existing in magnets too, can bring a new perspective to thermal control in devices.

Mpemba effect is a paradoxical phenomenon in which a hot liquid can cool or freeze faster than a cold liquid under certain conditions. The effect described by Aristotle, in his book Meterologica, was rediscovered in 1960s by Erasto Mpemba, a schoolboy then in Tanzania.

Recently, the topic has been drawing attention of scientists from diverse domains. Even though there are efforts to investigate the effect in systems other than water, theoretically as well as experimentally, the reason behind its occurrence remains a puzzle.

Within the active research domain of magnetism and magnetic materials, the kinetics of transition of the paramagnets (manifesting temporary weaker attraction because atomic magnets align in random directions to provide zero net magnetization) to ferromagnetic phase (manifesting permanent stronger attraction because atomic magnets are ordered in the ferromagnetic phase, giving nonzero spontaneous magnetization), with lowering of temperature, became an important topic of research.

Scientists from Jawaharlal Nehru Centre for Advanced Scientific Research (JNCASR), an autonomous institute of Department of Science and Technology, studied such magnetic transitions and found that hotter paramagnets undergo faster transitions to their ferromagnetic phases.

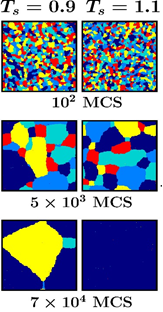

The team of researchers investigated the phenomena, which they called Mpemba effect in magnets, from the perspective of simple model systems. They chose to study the para- to ferromagnetic transitions, separated by a “critical” temperature, called the Curie point, in a few well-known model systems. These simple models served as good prototypes for understanding of a multitude of experimentally observed phenomena of different types. They exhibit transitions near which there exists enhancement of correlations in the structure. The team exploited this fact to identify the reason and capture a universality.

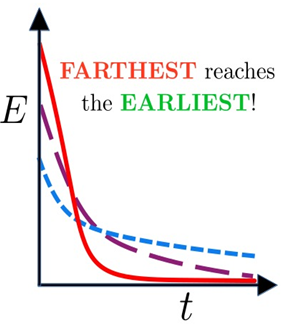

The researchers have chanced upon the interesting universal picture showing that the effect in these magnetic transitions appears due to the differences in the structure at various initial states. As the initial state point approaches the critical point, atomic magnets in the initial configurations tend to be correlated with each other over longer distances. Thus, the “transformation of a hotter paramagnet quicker into a ferromagnet” implies that systems initially having less spatial correlation order faster.

This is because, for initial configurations with large correlations, a significant early time is spent in destroying this correlation and catching up with that expected at the final temperature.

Given that such critical phenomena are ubiquitous in nature, systems of several varieties, including those related to societies and active matters, should be candidates for exhibiting this fascinating effect. Identifications of these, in addition to providing new knowledge, at the fundamental level, can lead to diverse applications such as giving a new perspective to thermal control in devices or defining better cooling strategies or even deriving beneficial rules in dynamics within living populations in crucial situations, say, during the spread of an epidemic.

Publication:

URL: https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevE.110.L012103

DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevE.110.L012103

Contact details for Media:

Author Name: Prof. Subir K. Das; Email ID: das[at]jncasr[dot]ac[dot]in;

Fig.: A system with higher initial temperature, having a higher initial energy, arrives at the final equilibrium, corresponding to a low temperature, earlier.

Fig.: Faster ordering in systems starting from higher temperatures. Colors represent domains with ordering in different directions.