Astronomers have unveiled an intriguing secret behind the dusty veil of a young star named T Chamaeleontis, quietly forming planets about 350 light-years from Earth when part of its circumstellar inner wall collapsed partially. This can help rewrite our understanding of how planetary systems evolve.

T Chamaeleontisan (T. Cha) is an extraordinary star is no ordinary young star. It is surrounded by a planet-forming disk called circumstellar disk that contains a wide gap—likely carved out by a newborn planet. Normally, the dense inner regions of such disks act like a protective wall or veil blocking much of the star’s ultraviolet light from reaching the colder, outer regions. That shielding makes Poly Atomic Hrydrocarbons (PAHs), flat, honeycomb-shaped molecules (Benzene rings) made of carbon and hydrogen thought to be among the earliest precursors of life’s chemistry, especially hard to detect around low-mass, Sun-like stars.

While these molecules are common in interstellar clouds, detecting them in the disks of low-mass, Sun-like stars has been challenging due to the low amount of ultra violet light produced by them

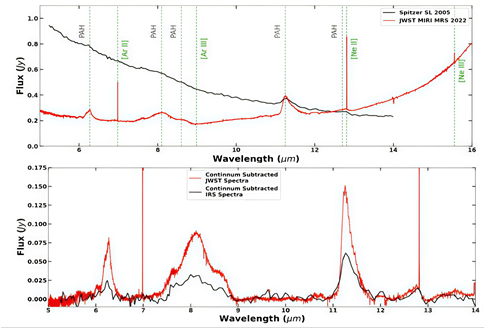

Fig 1: Top panel: The MIR spectrum of T Cha observed by JWST (red) in 2022 along with that observed by Spitzer (red) in 2002, showing that the slope of the spectrum had changed due to the collapse of the inner wall of the stellar disk. Bottom panel: the continuum subtracted MIR data from JWST and Spitzer showing the various spectral emission bands from PAH molecules. The PAH signals are much stronger in 2022 but the relative intensities of the features have stayed nearly the same, evidence that the molecules themselves have remained stable over time.

Scientists from the Indian Institute of Astrophysics (IIA), an autonomous institute of the Department of Science and Technology (DST) used archival spectroscopic data from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) Mid Infrared Instrument (MIRI) to study polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the spectrum of this star.

The ultra-sensitive JWST telescope, almost by accident, caught the moment in 2022 when that veil thinned—and an ancient kind of chemistry lit up in space. The material from the disk of the star suddenly plunged onto the star in a burst of accretion, thinning or partially collapsing that inner wall. As this happened ultraviolet radiation suddenly streamed outward, illuminating parts of the disk that were once in shadow. This helped shed light on the survival and variation of complex hydrocarbon molecules in the planet-forming disk around a young, Sun-like star.

T Cha is known to host a gap in its circumstellar disk that surrounds the central star, and this disk is believed to be caused by an emerging protoplanet.

This gap makes the system a key target for studying how young planets interact with their natal disks and shape their surrounding environments during the early stages of planet formation.

They absorb ultraviolet photos from the central star, and produce broad emission bands in the mid-infrared from 5 - 15 microns.

"JWST’s MIRI has now revealed them clearly in T Cha and this is one of the lowest mass stars with PAH detection in their circumstellar disk”, said Arun Roy, a post-doctoral fellow at IIA.

What makes this finding published in the Astronomical Journal extraordinary is the role of a dramatic change in the star’s circumstellar disk during its collapse due to high accretion event.

T Cha was observed by JWST in 2022, when inner wall had partially collapsed allowing ultraviolet photons to flood the outer disk.

Fig 2: An artist’s illustration of the JWST mirrors along with the PAH molecular structure (credits: JWST)

“This sudden illumination excited the PAHs in the disk, making them glow strongly in JWST’s detectors. It was like a curtain lifting, revealing chemistry that had been hidden for years,” says Arun Roy.

When Roy re-examined archival data from the Spitzer Space Telescope, he found faint but definite PAH signatures even then, making this the first confirmed detection of such molecules in Spitzer’s spectrum of T Cha. The comparison of the JWCT with archival data showed that while the PAHs grew brighter with JWST, their intrinsic properties such as charge and size remained unchanged over the two decades as seen by relative intensities of various PAH bands.

The study reports the PAH population in T Cha are smaller molecules with less than 30 carbon atoms in its structure.

“With JWST still in its prime, we can now revisit the disk of T Cha at multiple times, measuring how PAHs evolve with disk in time” Roy pointed out.

Publication link: 10.3847/1538-3881/adf637

For further information, please contact: scope[at]iiap[dot]res[dot]in