PathGennie, a novel computational framework developed by scientists can significantly accelerate the simulation of rare molecular events.

Published in the Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, this open-source software offers a breakthrough for computer-aided drug discovery (CADD) by predicting how potential drugs unbind from their protein targets without the artificial distortions common in standard methods.

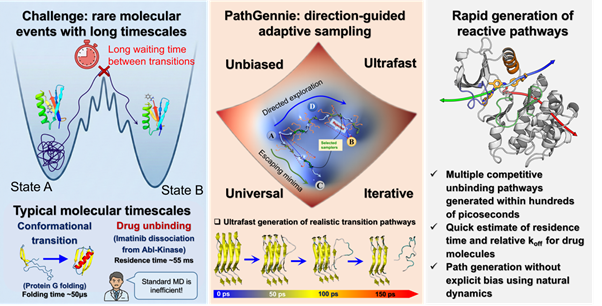

In the development of new pharmaceuticals, understanding the “residence time”—how long a drug molecule stays attached to its target protein—is often more critical than binding affinity alone. However, simulating the unbinding process (the drug leaving the protein pocket) is computationally expensive. These “rare events” happen on time scales of milliseconds to seconds, which is challenging or even impossible to access using standard classical molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, even with the most powerful supercomputers.

Traditionally, scientists force these events to happen by applying artificial bias forces or elevated temperatures, which can distort the physics of the interaction, leading to inaccurate predictions of the transition pathways.

Fig: The Solution: Direction-Guided Adaptive Sampling

Researchers at S. N. Bose National Centre for Basic Sciences, Kolkata, an autonomous institute of Department of Science and Technology (DST), have created the algorithm PathGennie which mimics natural selection on a microscopic scale instead of forcing the molecule to move.

It launches swarms of ultrashort, unbiased molecular dynamics trajectories – each only a few femtoseconds long – and then intelligently extends only those trajectories that make progress toward a desired outcome.

In essence, it acts like a direction-guided “scouting” mission in the molecule’s conformational landscape: numerous tiny simulation snippets are initiated, and those that move closer to a defined end state are selectively prolonged, while unproductive ones are discarded. This “survival of the fittest” approach for trajectories allows the algorithm to bypass the long waiting times of rare events without applying external biases or elevated temperatures, so the true kinetic pathways are retained. The method is general and can operate in any set of collective variables (CVs) – essentially any coordinates or features chosen to describe progress – including high-dimensional or machine-learned CV spaces. By dynamically balancing exploration and exploitation, PathGennie quickly zeroes in on transition pathways that would otherwise require prohibitively long simulations to discover.

In proof-of-concept studies, PathGennie created by a team led by Prof. Suman Chakrabarty, along with Dibyendu Maity and Shaheerah Shahid, has demonstrated the ability to uncover multiple competing pathways for several challenging molecular systems. For example, it rapidly mapped out how a benzene molecule escapes from the deep binding pocket of the T4 lysozyme enzyme, revealing a network of distinct ligand exit routes. Similarly, the algorithm identified three separate dissociation pathways for the anti-cancer drug imatinib (Gleevec) as it unbinds from the Abl kinase, recovering all the routes previously reported in the literature with just a few iterations. These ligand unbinding pathways were found without any steering forces, yet matched the mechanisms seen in earlier biased simulations and experiments, validating PathGennie’s accuracy.

Because PathGennie is a general-purpose framework, it can be adapted to a wide range of rare events beyond those tested so far. The authors note it is immediately applicable to problems such as chemical reactions, catalytic processes, phase transitions, or self-assembly phenomena – essentially any scenario in which one needs to find a transition pathway over a high energy barrier. It is also compatible with modern machine-learning techniques; for example, one could use machine-learned order parameters as the collective variables guiding the sampling. This flexibility ensures that PathGennie can be integrated into diverse simulation pipelines. The software has been made freely available to the scientific community, lowering the barrier for other researchers to leverage this technique.

Publication link: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jctc.5c01244

For more details contact Prof. Suman Chakrabarty at sumanc[at]bose[dot]res[dot]in