Careful modelling of the thermal and ionization structure of a type of celestial body called planetary nebulae with data from Vainu Bappu Telescope in Kavalur enabled astronomers to gain better insights into the formation and evolution of these hydrogen deficient stars.

Planetary Nebulae are gas and dust shells ejected by stars like our Sun after they exhaust hydrogen and helium fuel in their cores-- something that our own Sun is expected to do 5 billion years from now. As the stellar core shrinks due to lack of nuclear energy generation, it becomes hotter and radiates more intensely in far-ultraviolet, and resembled planets when viewed by astronomers with small telescopes more than a century ago.

While most stars in this older phase of their lives produce cores (the central stars) with tiny residual hydrogen envelopes, around 25% of them show a deficiency of hydrogen but are rich in helium at their surfaces instead. A subset of them can also display strong mass-loss and emission lines of ionised helium, carbon and oxygen technically called Wolf-Rayet (WR) characteristics.

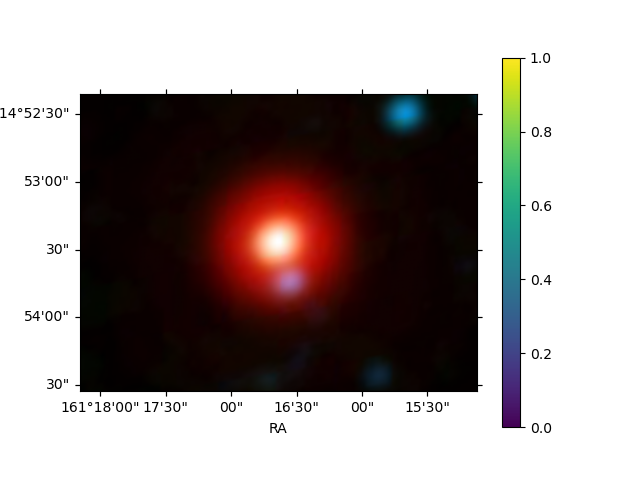

Planetary Nebula PN IC 2003 is one of those rare Planetary Nebulae which has a hydrogen-deficient central remnant star of Wolf Rayet type.

While the evolutionary status of normal central stars of planetary nebulae is understood reasonably well, how and when a central star can become hydrogen-poor is largely unknown. The processes governing the formation and evolution of such objects are imprinted in the planetary nebular gas surrounding them, and hence their physical and chemical structures are required to be studied in detail.

In order to understand this problem better, astronomers from the Indian Institute of Astrophysics (IIA), an autonomous institute of Department of Science and Technology observed IC 2003 using the optical medium-resolution spectrograph (OMR) attached to the 2.3-m Vainu Bappu Telescope at the Vainu Bappu Observatory in Kavalur, Tamil Nadu, operated by IIA.

“We also used the ultraviolet spectra from the IUE satellite and the broadband infrared fluxes from the IRAS satellite from their archive for this study”, said K. Khushbu, the lead author and a Ph.D. student. Together these observations could accurately underline the relative importance of gas and dust in deciding the thermal structure of the nebula. This in turn helped them to derive accurate central star parameters, which are important to explain the origin of this object.

The models used by the Astronomers, showed that the derived parameters of the nebula and the ionising source (mass and temperature) differed significantly from those derived by dust-free models.

“This study highlights the importance of dust grains in the thermal balance of ionised gas and it explains the origin of large temperature variation required in resolving abundance discrepancies usually observed with the ionised gas associated with astrophysical nebulae”, said Prof. C. Muthumariappan, supervisor and co-author of the study. “We used a one-dimensional dusty photo-ionisation code CLOUDY17.3 to simulate data from ultraviolet, optical and infrared observations”, he added.

By accurately modelling the photo-electric heating of the nebula by the dust grains, they were able to reproduce the thermal structure of the planetary nebula derived from observations. “We could even reproduce the large temperature gradient usually seen in the nebula with WR stars. Our determination of abundances of elements like helium, nitrogen, oxygen are significantly different from the values obtained empirically”, said Khushbu.

Accurate grain size distribution in the nebula was also derived, and a proper treatment of photo-electric heating of grains was shown to be crucial to explain temperature variation. They also derived accurate values of luminosity, temperature and the mass of the central star from this study. The initial mass was derived to be 3.26 times the mass of the Sun, suggesting a higher mass Star.

Publication link: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2024.04.058